The envelope sat on Elena's desk for three days before she opened it.

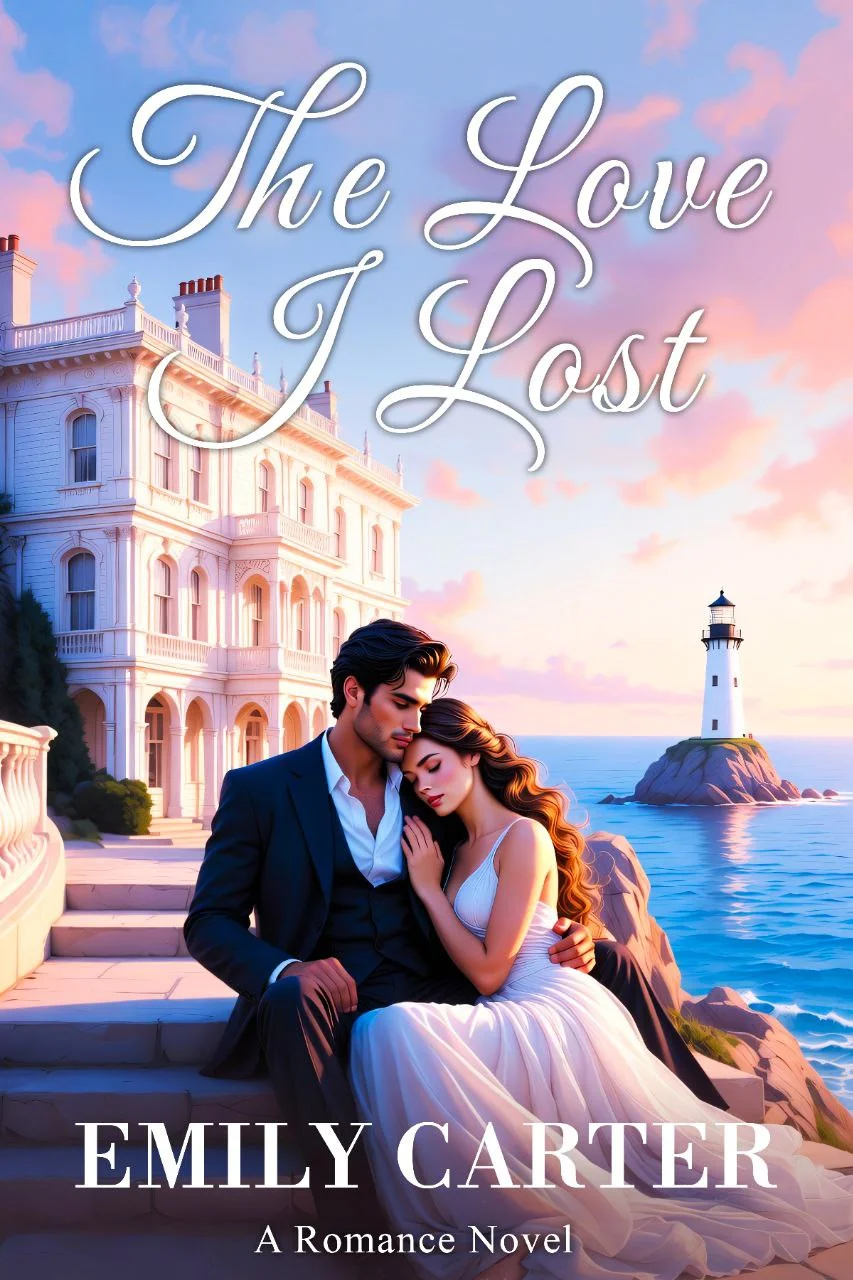

It wasn't that she didn't recognize the return address. She recognized it immediately, the way a body recognizes the particular ache of an old injury when the weather changes. Harborview Inn, Pemaquid Point, Maine. The handwriting was unfamiliar, cramped and elderly, but the location needed no introduction. That address had lived in some quiet corner of her mind for a decade, surfacing in dreams she pretended not to remember and in the occasional sharp stab of memory triggered by the smell of salt air or the sight of hydrangeas blooming blue against weathered shingles.

On the fourth day, a Tuesday morning that arrived gray and relentless with late March rain, Elena finally slid her finger beneath the seal.

The letter inside was brief and handwritten on cream stationery embossed with a small lighthouse. The writer introduced herself as Dorothy Whitmore, owner and operator of the Harborview Inn, and she had a proposition. She'd seen Elena's work featured in Architectural Digest, the restoration of a Back Bay townhouse that had earned Elena her first significant recognition. Mrs. Whitmore was preparing to restore the inn after years of deferred maintenance, and she wanted Elena to lead the interior design. The budget was generous. The timeline was tight—eight weeks, beginning in April, to prepare for the summer season. And there was something else, Mrs. Whitmore wrote, something that couldn't be adequately explained in a letter. She hoped Elena would come see for herself.

Elena read the letter twice, then set it down and walked to her office window. Her design studio occupied the third floor of a converted warehouse in Boston's South End, and from this vantage point she could see the city sprawled beneath the pewter sky, slick with rain and stubbornly awake despite the early hour. She'd built this life carefully, brick by brick, project by project. After the disaster with the Morrison account six months ago—a clash of visions that had ended with her name quietly removed from a project she'd poured two years into—she needed a win. Something unambiguous. Something she could point to and say, I made that beautiful.

The Harborview Inn could be that project. The building itself was remarkable, a Queen Anne Victorian perched on the rocky Maine coast with original millwork, fourteen guest rooms, and the kind of faded grandeur that made Elena's fingers itch for fabric swatches and paint samples. She'd researched it compulsively over the past three days, telling herself she was simply being thorough, that any designer would do the same. The inn had been built in 1892 by a sea captain for his bride. It had survived two fires, a hurricane, and the slow economic decay of coastal tourism in the mid-twentieth century. It had ghosts, probably—not literal ones, though Elena wouldn't have been surprised. Every building that old carried its history in the walls.

But this building also carried hers.

She pressed her palm flat against the cool window glass and watched the rain slide down in crooked paths. She was thirty-two years old. She had built a successful business, cultivated a reputation for thoughtful restoration work that honored the past while serving the present, and learned to sleep through most nights without waking to the echo of a door closing. She had done the work, as her therapist liked to say. She had moved on.

So why did her hand tremble when she picked up the letter again?

The practical answer was simple: she needed this job. The Morrison disaster had shaken client confidence, and while her pipeline wasn't empty, it wasn't full either. A project like the Harborview, with its potential for press coverage and its alignment with her professional strengths, could reestablish her as a leader in historic preservation design. She'd be a fool to turn it down because of something that had happened ten years ago, when she was practically a different person, when she had been young enough to believe that love was a thing you could hold in your hands.

The impractical answer was harder to articulate. It had something to do with the way her chest tightened when she thought about the inn's wraparound porch, the view of the lighthouse from the east-facing windows, the particular quality of light in the late afternoon when the sun sank toward the water and turned everything gold. She had spent only three days there, a long weekend at the end of the summer between her junior and senior years of college. Three days shouldn't have the power to shape a life. Three days shouldn't still ache.

But they did.

Elena turned away from the window and sat down at her desk. She pulled up her calendar, her email, her project management software. She was a professional. She made decisions based on data, on strategic advantage, on the long game. And the long game said she should take this job, collect the fee, do excellent work, and add another triumph to her portfolio. Whatever ghosts waited for her in Maine, she had outgrown them.

She typed a reply to Dorothy Whitmore before she could lose her nerve.

• • •

The drive from Boston to Pemaquid Point took nearly four hours, and Elena spent most of it rehearsing what she would say when she arrived. She had accepted the job via email two weeks ago and had exchanged several more messages with Mrs. Whitmore about logistics, timelines, and design preferences. The older woman wrote the way she seemed to think—in warm, meandering sentences full of digressions and exclamation points—and Elena found herself charmed despite her apprehension. Mrs. Whitmore had owned the inn for over forty years. She spoke of it the way some people spoke of their children, with exasperated devotion and an unshakeable faith in its potential.

What Mrs. Whitmore had not mentioned, in any of their correspondence, was the architect.

Elena learned about him from the project brief that arrived in her inbox three days before her departure. The structural and exterior restoration work would be handled by Marcus Sullivan of Sullivan Historic Preservation, based in Portland. Elena read his name, and then she read it again, and then she closed her laptop and went for a run along the Charles River until her lungs burned and her mind went mercifully blank.

Marcus Sullivan. Of course.

She had known, on some level, that he'd stayed in New England. She had carefully avoided knowing the specifics, but the architecture and preservation world was small, and his name surfaced occasionally in trade publications and award announcements. She knew he had built something impressive in the decade since she'd last seen him. She knew he specialized in exactly the kind of work the Harborview would require. She should have anticipated this.

But anticipation and reality were different beasts, and reality was that in three days she would be standing in the same building as the only man she had ever truly loved, trying to pretend that her hands weren't shaking and her heart wasn't attempting to escape through her throat.

She had considered backing out. For approximately four hours, she had drafted and deleted a dozen apologetic emails to Mrs. Whitmore explaining that a scheduling conflict had arisen, that she regretfully could not take on the project after all. But each time her fingers hovered over the send button, something stopped her. Pride, maybe. Stubbornness. Or perhaps it was something deeper—a small, persistent voice that whispered she had spent ten years running from this particular ghost, and running was getting exhausting.

So she packed her car with sample books and sketching supplies, her laptop and her anxiety, and she drove north.

The Maine coastline revealed itself gradually as she left the highway and wound along increasingly narrow roads. The landscape shifted from suburban sprawl to dense forest to sudden, startling glimpses of gray-blue water between the trees. The April air was cold but softening toward spring, and the light had that particular quality she remembered from years ago—clear and pale and somehow both gentle and unforgiving. This was not a coast that prettified itself for visitors. It demanded to be taken on its own terms.

Elena's GPS guided her down a final gravel road, and then the trees parted and there it was: the Harborview Inn.

She pulled over to the shoulder and stopped the car, not quite ready to arrive.

The building rose against the sky like something from another century, which of course it was. Three stories of dove-gray shingles and white trim, a turret on the southeast corner, and the wraparound porch she remembered as clearly as her own childhood bedroom. The windows caught the afternoon light and threw it back in fragments, and the hydrangeas were still brown and dormant but promised blue riots in a few months' time. Beyond the inn, the Atlantic stretched to the horizon, restless and eternal.

It was more beautiful than she had allowed herself to remember.

She sat there for several minutes, her hands on the steering wheel, her breath fogging the window. Somewhere inside that building, Marcus might already be waiting. Or perhaps he wouldn't arrive until tomorrow. She hadn't asked for the specifics of his schedule, and Mrs. Whitmore hadn't offered them. The uncertainty felt unbearable.

A knock on her window made her jump.

The woman standing beside her car was small and white-haired, wrapped in a blue wool cardigan that looked hand-knit and possibly older than Elena herself. Her face was lined and kind, with sharp dark eyes that seemed to be measuring something carefully.

Elena rolled down the window.

"You must be Elena Reyes," the woman said. Her voice was exactly as warm as her emails, with the slight Down East accent that Elena associated with rocky shores and lobster boats and people who had been shaped by generations of hard weather. "I'm Dorothy. I was starting to think you'd gotten lost."

"I stopped to look at the building," Elena admitted. "I wasn't expecting it to be quite so..."

She trailed off, uncertain how to finish the sentence. Dorothy smiled as though she understood anyway.

"She has that effect on people," the older woman said. "The inn, I mean. I remember the first time I saw her, forty-three years ago. I'd come up from Massachusetts with my husband for a weekend, and by Sunday I'd made him an offer on the place. He thought I'd lost my mind." Her smile turned wistful. "He was probably right. But here I am."

Elena climbed out of the car, pulling her jacket tighter against the salt-tinged wind. Up close, Dorothy Whitmore had the particular elegance of women who have lived long enough to stop caring what anyone thinks, her white hair pinned up carelessly and her cardigan buttoned wrong and her posture suggesting that she answered to no one but herself.

"The building has good bones," Elena said, falling back on professional language. "I did some research before I came. The original architect was James Howard, wasn't he? He did several other houses along this stretch of coast."

"You've done your homework." Dorothy looked pleased. "Howard understood this landscape. He knew the buildings had to be sturdy enough to survive but beautiful enough to justify the survival. Not many architects manage both."

She began walking toward the inn, clearly expecting Elena to follow. Elena grabbed her bag from the backseat and fell into step beside her, trying not to look too obviously at every window for a familiar silhouette.

"Marcus said the same thing," Dorothy added casually. "About Howard's work. You two will have a lot to talk about."

Elena's stride faltered. "Marcus is here already?"

"Arrived this morning. He's up in the attic right now, examining the support beams. Something about wanting to understand the structural logic before he proposes any changes." Dorothy glanced at Elena with an expression that was difficult to read. "I assume you two have worked together before?"

The question was innocent. It had to be innocent. Mrs. Whitmore could not possibly know.

"Not professionally," Elena heard herself say. "We were... acquainted. A long time ago."

Dorothy nodded slowly, as though this confirmed something she had already suspected. "A long time ago can feel like yesterday, in the right building. Old houses have a way of keeping time differently than the rest of the world."

Before Elena could unpack this cryptic statement, they had reached the front porch. The steps creaked familiarly under her feet—she remembered that creak, had catalogued it among the sensory details of that long-ago weekend without consciously intending to—and then they were through the front door and standing in the entrance hall.

Elena stopped breathing.

The inn's interior was faded but magnificent. A grand staircase swept upward toward a stained glass window that filtered the light into jewel tones across the worn hardwood floors. The wallpaper was peeling in places, revealing older paper beneath, and the ceiling medallion above the brass chandelier was missing several pieces, but the proportions of the space were perfect. Generous without being overwhelming. Elegant without being cold.

And at the top of the staircase, one hand on the banister, stood Marcus Sullivan.

He looked older. Of course he did. Ten years would mark anyone. But the changes were subtle: a few lines around his eyes, a more settled quality to the way he held himself, the kind of physical confidence that came from a decade of knowing who he was and what he could do. His dark hair was shorter than she remembered, and he wore a flannel shirt and work boots that suggested he'd already been examining more than just attic beams. But his eyes were the same. Deep brown, almost black, with that particular intensity that had always made Elena feel as though he was seeing something in her she couldn't see in herself.

Those eyes were fixed on her now, and she could not read what was in them.

"Elena," he said. Just her name. No inflection she could decipher.

"Marcus." Her voice sounded strange to her own ears. Thin. Too controlled.

Dorothy looked between them with an expression that might have been satisfaction or might have been concern—Elena couldn't tell which, and didn't have the bandwidth to analyze it. "Well," the older woman said briskly, "I'll give you both a moment to get reacquainted. Elena, your room is the second door on the right at the top of the stairs. I've put Marcus in the east wing. Dinner's at seven if you're hungry."

She disappeared through a doorway that presumably led toward the kitchen, and Elena was left standing in the entrance hall with Marcus still frozen on the staircase above her.

The silence stretched between them, vast and terrible.

"I didn't know you'd be here," Elena finally said. "When I accepted the job. I didn't know."

Marcus descended the stairs slowly, each step measured and deliberate. "Neither did I."

"If you want me to leave—"

"Why would I want that?"

She didn't have an answer. Or rather, she had too many answers, none of which she could articulate in this moment, in this building, with the late afternoon light making everything golden and painful.

He stopped a few feet away from her, close enough that she could smell sawdust and something else, something that memory supplied before her conscious mind could catch up. He had always smelled like sandalwood. Apparently that hadn't changed.

"It's been ten years," he said.

"I know."

"You look..." He paused, as though reconsidering his words. "You look well, Elena."

It was such an inadequate thing to say. Such a small container for everything that had happened between them, everything that hadn't happened, everything that might have been. But perhaps inadequacy was all they had right now—the safe, professional language of former acquaintances who had once been something more.

"Thank you," she said. "So do you."

He nodded, and then his gaze shifted to something over her shoulder—the doorway, maybe, or the stained glass window, or simply anywhere that wasn't her face. "We should probably talk about how this is going to work. The project, I mean. If we're going to be working together."

"Yes. We should."

"Maybe tomorrow. Once we've both had a chance to settle in."

"That sounds reasonable."

The conversation was excruciating in its civility, and Elena wanted to scream or cry or demand that he explain why he had stopped calling, why he had let her wait for a response that never came, why he had simply vanished from her life as though their three years together had meant nothing at all. But she had learned, in the decade since, that some questions had no good answers, and some wounds only reopened when you probed them.

"I'll see you at dinner, then," she said.

"Dinner. Right." He was already retreating up the stairs, and she watched him go, cataloguing the new things and the familiar things and the ache that hadn't diminished one bit in all this time.

When she finally climbed the stairs herself and found her room—a corner suite with a view of the lighthouse and a four-poster bed and faded floral wallpaper that would need to be replaced—she sat on the edge of the mattress and pressed her hands to her face.

She had made a terrible mistake in coming here. Or perhaps this was the best decision she had ever made. The problem with ghosts was that you could never be sure if they wanted to haunt you or heal you, and sometimes, Elena thought, they wanted both.

Through the window, she could see the ocean turning colors as the sun began its descent, and somewhere in this old house, Marcus was thinking thoughts she would never know, and the summer stretched ahead of them both—uncertain, inevitable, full of everything they had lost and everything they might, against all odds, find again.

• • •

End of Chapter One